|

Frisian

Gysbert

Japicx (1603-1666),

Gysbert

Japicx (1603-1666),

pioneer in using and promoting

Frisian as a literature language |

Language information:

The Frisians may well be called “the North Sea People.” Most of their early history remains a mystery. However, their physical survival

under the onslaughts of the frequently stormy North Sea and their faithfulness

to their ethnicity as a long-time minority is generally regarded as nothing

short of remarkable. Their ancestors are widely considered associated with

the Bronze Age Elp Culture

(1800–800 BCE). Frisians used to inhabit the European Lowlands coast from just south

of what is today’s Netherlands-Belgian border to the mouth of River Elbe in

what

is

now

Northern

Germany. Even though their language and culture, technically speaking, became

extinct in most areas, they left marked imprints on the Dutch and Low Saxon

languages

and cultures that replaced them.

The traditional

Frisian area later came to be extended along  the west coast of the Jutish peninsula

to just north of today’s German-Danish border. Simply speaking, this extension

from western regions occurred in two stages: around 700 CE and around 1100 CE.

The Frisian dialect spoken by the first group of settlers survived and further

developed on the islands while

the mainland

and its tideflats islands came to be dominated by the Frisian dialect imported

by the second wave of immigrants. the west coast of the Jutish peninsula

to just north of today’s German-Danish border. Simply speaking, this extension

from western regions occurred in two stages: around 700 CE and around 1100 CE.

The Frisian dialect spoken by the first group of settlers survived and further

developed on the islands while

the mainland

and its tideflats islands came to be dominated by the Frisian dialect imported

by the second wave of immigrants.

This and relatively

little communication between

islanders and mainlanders account for marked

differences between the insular and continental dialects of North Frisian.

Within the

other,

previously

contiguous Frisian language area there used to be a dialect continuum. This once smooth continuum came to be disrupted when the area came

to

be

devided

up

into

enclaves

due

to

Dutch

and Saxon encroachment. Dialect islands now developed with little communication with each other, and dialectical divergence increased.

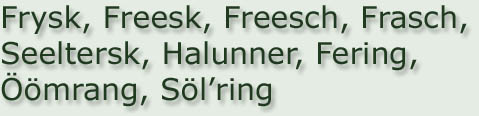

Surviving Frisian varieties are the following:

| · |

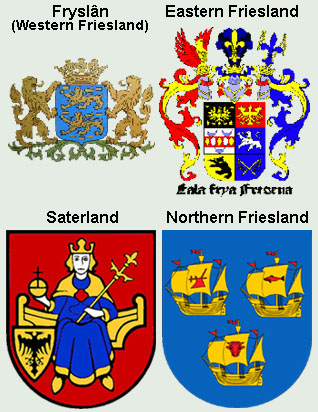

WEST FRISIAN ((Westerlauwersk) Frysk)* |

| |

· |

Standard Frisian (Standertfrysk) |

| |

· |

Clay Soil Frisian (Klaaifrysk) |

| |

· |

Woodlands Frisian (Wâldfrysk) |

| |

|

· North Woodlands Frisian (Noardhoeks) |

| |

· |

South Frisian (Súdhoeks) |

| |

· |

Southwest Frisian (Súdwesthoeksk) |

| |

· |

Schiermonnikoog Frisian (Skiermûntseagersk) |

| |

· |

Hindeloopen Frisian (Hynljippen) |

| |

· |

Terschelling (Skylge) Frisian |

| |

|

· East Terschelling Frisian (Aasters) |

| |

|

· West Terschelling Frisian (Schyllingers) |

| · |

EAST FRISIAN (mostly extinct) |

| |

· |

Sater Frisian (Seeltersk)* |

| · |

NORTH

FRISIAN |

| |

· |

Mainland North Frisian* |

| |

|

· Mooring/Bökingharde

Frisian (Böökinghiirderfrasch) |

| |

|

· Goesharde Frisian (Gooshiirderfreesch) |

| |

|

· South Goesharde Frisian (Sud-Gooshiirder) |

| |

|

· Central Goesharde Frisian (Middel-Gooshiirder) |

| |

|

· North Goesharde Frisian (Noard-Gooshiirder) |

| |

|

· Karrharde Frisian (Karrhiirderfreesch) |

| |

|

· Wiedingharde

Frisian (Wiringhiirderfreesk) |

| |

|

· Tideflats Islands (Halligen)

Frisian (Freesk) |

| |

· |

Island North Frisian |

| |

|

· Heligoland (Lunn) Frisian (Halunder)* |

| |

|

· Föhr-Amrum Frisian (Fering-Öömrang)* |

| |

|

· Föhr (Feer) Frisian (Fering) |

| |

|

· Amrum (Oomram) Frisian (Öömrang) |

| |

|

· Sylt (Söl) Frisian (Söl’ring)* |

___

* May be considered discrete languages |

Some of the varieties, especially those used in Germany, are endangered. Severely

threatened is the survival of Tideflats North Frisian.

Frisian has been

written since about the 8th century CE. Old Frisian was predominantly used for

religious and legal texts. The Middle Frisian period lasted until 1820, with

more linguistic and literary variety. East Frisian began fading away early, due

to Middle Saxon encroachment. What is now Eastern Friesland became predominantly

Low-Saxon-speaking. Today’s Low Saxon varieties of Eastern  Friesland, misleadingly referred to

as “East Frisian,” have noticeable Frisian substrata which make them a special branch among the

Northern Low Saxon dialects. This applies to the Low Saxon varieties in the Netherlands

province of Groningen as well. Friesland, misleadingly referred to

as “East Frisian,” have noticeable Frisian substrata which make them a special branch among the

Northern Low Saxon dialects. This applies to the Low Saxon varieties in the Netherlands

province of Groningen as well.

The only surviving

varieties of Eastern Frisian are those of Sater Frisian of the Saterland region

south

of

Eastern Friesland, where staunchly Roman Catholic Frisians formed an enclave

during the Christian Reformation.

These varieties

came to dominate among the local indigenous Westphalian-Low-Saxon-speaking farmers

as well.

It

is

quite

possible

that

the local Frisian varieties

absorbed

some indigenous Saxon features and that Sater

Frisian has Low Saxon

substrata.

What outside the

Netherlands is called “West Frisian” is called “Westerlauwer Frisian” in the Netherlands (Westerlauwersk Frysk in Frisian, and Westerlauwers Fries in Dutch). These are the Frisian varieties used west of the Lauwers river

in the province of Fryslân (formerly called Friesland in Dutch) and parts of the province of Groningen (West Frisian Grinslân, Low Saxon Grönnen). What is called West-Fries (“West Frisian”) in Dutch has come to denote a number of Dutch dialects on Frisian substrata

used in

the province of North Holland.

While these days

all surviving varieties of Frisian are officially recognized within the framework

of the European Languages Charter, the varieties used in Germany are struggling

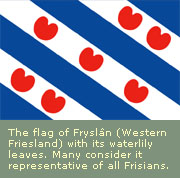

to survive. West Frisian is doing relatively well due to a comparably large number

of speakers (ca. 350,000 native speakers) and fervent efforts on the part of

language activists and the provincial administrations. The language is used in

the mass

media and

in

schools, and there are printed and electronic publications, including modern

entertainment

material, in West Frisian. The language is used in

the mass

media and

in

schools, and there are printed and electronic publications, including modern

entertainment

material, in West Frisian.

Because of its relatively

sizeable speaker community and its relatively secure and prominent position,

West Frisian tends to be considered representative as simply “Frisian”, especially among Netherlanders,

including non-Frisians. It behooves everyone to bear in mind that Frisian of

the Netherlands is not the only type. Lately, inter-Frisian communication and

common

activities have been helping to propagate the notion of a more widespread and

diverse Frisian world, and East Frisians tend to be included in this as ethnic

Frisians despite the fact that most of them have lost their

ancestral

Frisian

language.

There are some Frisian-speaking,

mostly West-Frisian-speaking,

communities outside Europe, particularly in North America, Australia and New

Zealand, as well as in overseas parts of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

The Frisian languages

are considered

the closest relatives of the Anglic languages (English and Scots), and some speak of an Anglo-Frisian branch among the West Germanic languages.

While the languages of the Angles and Saxons are routinely mentioned in connection

with the genesis of Old English (or Anglo-Saxon), Frisian is rarely mentioned

although it evidently participated in the process, apparently more so than did

the other two languages. One reason for what appear to be Frisian elements in

English

and scarcity of officially mentioned Frisian presence in medieval Britain might

be that Anglic, Saxon and Jutish colonists took with them across the Channel

Frisian-speaking women who raised their British-born children.

Gerhard Willers’s

remarks about Sater Frisian:

“When

I still lived in Cologne I learned Sater Frisian through self-study only with

the help of a Sater Frisian reading book for schools and a dictionary (Sater

Frisian-German), but my good knowledge of Northern Low Saxon helped me a lot

to learn it quickly.

I strongly believe that Sater Frisian has a Low Saxon (Westphalian) substrate.”

“Sater

Frisian is only spoken in the municipality of Saterland, which is situated

in the Northwest of the Landkreis (district) of Cloppenburg or on the other hand

in the Southeast of the town of Leer, Lower Saxony. The municipality of Saterland

consists of the villages Strukelje (Strücklingen), Roomelse (Ramsloh), Schäddel

(Scharrel) and Sedelsbierich (Sedelsberg). The estimated number of the speakers

of Saterfrisian is 2000. There are some slight differences with respect

to

vocabulary and pronunciation of Sater Frisian between the places Strücklingen,

Ramsloh and Scharrel. But this does not prevent mutual intelligibility of the

Saterland people when speaking Sater Frisian. But for the Low Saxon and German

speaking population of the neighbouring villages, Sater

Frisian is completely

unintelligible.”

“For

me the most striking features of Saterfrisian are its melodic sound,

(it has much more diphthongs and even some triphthongs than Low Saxon) and in

grammar the existence of two infinitives (like all other Frisian variants). Sater

Frisian

is a very old and conservative language, so it has preserved Frisian words that

are already extinct in other Frisian variantes, for example: Jool (English: wheel,

German: Rad) and it has even preserved Low Saxon words that are already extinct

in the present Low Saxon, for example: the German word Hühnerauge (corn on a toe) reads in modern

Low Saxon Höhneroog; and in Saterfrisian? Well, I admit, many people in Saterland

would say in Seeltersk Hanneoge. But there are also many people who say Liektouden, a cognate of Standard

German Leichdorn; and this is indeed a very, very old German word which is no

longer used in

Standard German of today, at least not in this area.”

“Well, dear Lowlanders and other readers of these lines, there

is really much more to tell you about this old and mysterious and melodious and

even thrilling language,

I assure you.”

Genealogy:

Indo-European > Germanic > West > Frisian

Historical Lowlands language contacts: Dutch, English, Low Saxon

Author: Reinhard

F. Hahnscots.php |